While dealing with corruption, it becomes challenging to establish a direct correlation between this vice and economic output or even anticipated deliverability. This is because the efforts bring to play “public sectors governance indicators, like the rule of law, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality” (OECD, n.d. p.2). Other components that also play a role include value creation. In addition, there are studies showing high levels of GDP growth amidst countries with high levels of corruption, hence the Asian paradox (p. 14). These complexities leave some wondering whether corruption is as big a vice as stated or if it should be combatted at all.

From the literature, it is evident that Kenya has made steps in combating corruption.

Nevertheless, per the Kenya Peer Review Report of May 2006, “Kenya has had, and continues to have, a significant problem of corruption” (APRM Secretariat, 2006, p. 25). What is it that makes this vice so elusive?

Evidently, there is plenty on paper, thanks to the Mwai Kibaki regime. However, this is certainly not enough (Hope, 2013).

-

Passivity and Docility:

When individuals tend towards passivity, they tilt towards condoning and accepting corrupt acts, becoming less averse to corruption (Gatti & Stefano–Rigolini, 2003); Nilsson, 2009).

There appears to be a defeatist attitude and a general acceptance that corruption is normal.

-

Contagious Corruption:

Corruption is not directly contagious. However, there is often a regional political, as well as language group culture that is part of African countries. Kenya’s borders have shared communities (North and North Eastern: -Oromo, Borana, Gabra, Turkana, Somalis; South:- Maasai; Western:- Karamojong, Acholi, Luos, Luhyas). What happens in Ethiopia, South Sudan, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Tanzania, affects Kenya.

This is the meaning of the quote, “neighboring countries share common political cultures and adopt similar institutions. These common political cultures are very close to [levels of] corruption” (Nilsson, 2009, p.3; Hillman & Swank, 2000; Becker et al., 2009).

This means that if a neighboring country has indicators that tilt towards nurturing corruption, Kenyans have to be concerned at the individual and national levels. Individuals and leaders in the concerned border regions need to have clear and deliberate mechanisms to stop the vice from spilling over.

-

Corruption mutates:

The changing faces of corruption (land injustices, tokenism, procurement, and advantaging), as well as the phases of corruption, discussed, show the challenges related to understanding corruption. Additional information is given under the title of what makes corruption elusive.

These issues make this paper tag the term mutation, on corruption, thus making it even harder to tackle.

This sheds light on the following section what needs to be done to counter corruption in Kenya?

What Needs to be Done to Counter Corruption in Kenya?

In Kenya, Hope (2013, p. 298) states that the fight against corruption has not been won because of:

-

A lack of cooperation and goodwill from concerned government officers and institutions;

-

The inability to enforce its recommendations and compel public officers to respond to Public Complaints Standing Committee (PCSC) inquiries and concerns;

-

The presence of manual systems of operation undermines internal efficiency.

In addition, Hope (2013) recommends transformational leadership; those who “inspire followers to change motivations, expectations, and perceptions to work towards common goals” (p. 300). She also advocates for deterrent punishment, as well as having in place reform strategies which include enhancement of “ethical behavior” and “public accountability” (p. 302).

She notes that political will is “impotent” (Hope, 1999).

There is also a need to enhance the institutionalization of transformation (Andrews, McConnell & Westcott, 2010).

Notably also, “corruption was [is] nurtured and perfected by those in authority. Parliament was [remains] impotent because the party threatened [threatens] those perceived as against the establishment with expulsions.

The judiciary was [is] compromised and it did [does] nothing to improve the situation…[it] was [is] also corrupt” (Anassi, 2004, p. 109). Also, there is a clear link between economic development (financial market), political stability, democracy, and corruption (Majeed, & MacDonald, 2011).

Based on these realities, what lessons can Kenya have from elsewhere?

-

Democracy:

The term democracy is understood as per Abraham Lincoln’s definition, “government of, by and for the people” (Nanjom, 2007, p. 3). With an empowered populace, through democracy, “Democratic nations … face lower degrees of corruption since corrupt officials, whether elected or appointed, face a threat of losing public office (i.e. their rent-seeking potential)… [it] offers unique rent-seeking opportunities in less democratic countries” (Goel & Nelson, 2008, p. 10). for this reality to be actualized, the public is called upon to exercise their oversight role.

Ultimately, this role is done at the ballot when the electorate decides on who to give the leadership mandate. A critical analysis of each leader is paramount, superseding ethnicity, clannism, gender, and even the individual’s economic power. That notwithstanding, there is a need for the electorate to remain vigilant throughout the five-year term. The leader needs to know and feel they are being watched by those elected. Only then, will they be kept on their toes in their performance on accountability and transparency (OECD, n.d)? Also, for there to be a rational decision-making process in elections, tokenism has to be kept in check since it undermines the electorates’ power to realize free and fair elections (Nayonjom, 2007).

-

Land issues:

The land is a source of wealth creation and accounts for the wealthy status of a significant number of persons who have been in leadership (Syagga, 2013). Subsequently, persons that have had (and continue to have) large pieces of land, and have thus, higher wealth, have been able to (and are more likely to) access education thus a correlation between land, poverty, and education (Gathiaka, 2021).

Their wealth has continued to advantage them over the rest of the citizenry. There is, therefore, an urgent cry that land injustices in Kenya, be dealt with, for there to be more equity and equality (Syagga, 2013). The continued land barons versus squatters as revealed through the different commissions on land issues in Kenya (Akiwumi Commission, 1999; GOK, 2008-Waki Commission) point towards the urgent need to deal with land issues as a way to counter corruption. Additional information on tackling issues of land and corruption is given by Transparency International (2015).

-

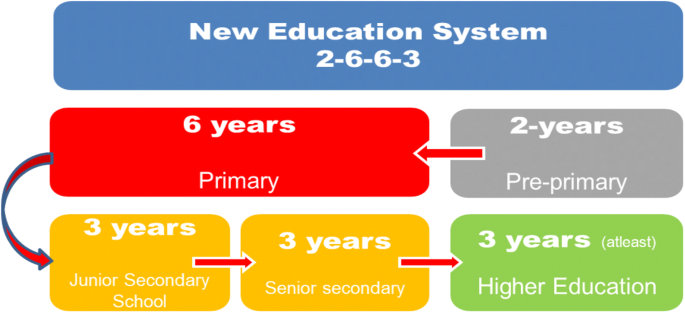

Education:

Education is seen as a value enhancer. It does so by nurturing honesty, hard work, diligence, and respect. It also contributes largely to equality (including gender equality), and factors facilitate low levels of corruption (Uslather & Rothstein, 2016). Also, “more educated people are likely to complain about corruption” (p. 229).

The importance of education in dealing with corruption is also noted in Reinikka and Svensson, (2005) and in Botero, Ponce, and Shleifer, (2012). Also, through education, “… all children were [are] taught to identify with the state and its goals and purposes rather than with local politics (estates, peasant communities, regions, etc.)” (Ramirez & Boli, 1987, p. 4). Children are taught to be together (p.34).

-

Religion:

This is seen as a contributor to lowered levels of corruption (Alesina, Amaud, William & Sergio, 2003; Samanta, 2011; Shadabi, 2013). This is in line with the religions’ ability to promote education (Uslather & Rothstein, 2016) which as noted in previous sub-titles is key in promoting values geared towards lowering corruption.

Inversely, when religion promotes passivity, it promotes corruption since its members are more docile and complacent when their leaders engage in corrupt dealings (Obaji & Ignatius 2015). For religion to contribute towards lowered levels of corruption, it should also encourage positive wealth creation (Anderson, 2019).

-

Free Press:

“ free press with a broad circulation is important for curbing corruption” (Uslaner & Rothstein, 2016, p. 230) (see also Brunetti & Weder, 2003). The traditional understanding of government was, engulfed with secrecy. Citizens are encouraged to continue engaging with government information to deal with corruption; knowledge is power (Adili, 2014). On the part of the government, it continues to be obliged to avail information to the public as indicated in the Constitution of Kenya (2010, Act 35):

Access to information 35. (1) Every citizen has the right of access to— (a) information held by the State; and (b) information held by another person and required for the exercise or protection of any right or fundamental freedom. (2) Every person has the right to the correction or deletion of untrue or misleading information that affects the person. (3) The State shall publish and publicize any important information affecting the nation (also cf the Official Secrets Act, 1992).

-

Economic Development:

There is a significant link between economic development and corruption. According to Majeed and MacDonald, (2011), “a standard deviation increase in financial intermediation is associated with a decrease in corruption of 0.20 points” (p. 1).

The authors also note that when markets operate with low competition, public officials have a tendency of demanding high premiums thus increasing corruption. This is referred to as non-collusive corruption (Foellmi & Oechslin, 2007). Nevertheless, other factors influence corruption levels as noted in the previous sub-titles.

Studies also take note of the use of corruption among leaders seeking bureaucratic positions, often with funds solicited from close associates. When this happens, the move widens the corruption stake (Boerner & Hainz, 2009).

-

Continued Citizen Vigilance:

Public participation is noted as the Citizen’s best weapon against graft (Adili, 2012). Based on the Constitution of Kenya (2010), Article 196 (1)(b) – “requires that

the county assembly facilitates public participation in the legislative and other business of the assembly.” In addition, Section 10(2)(a) includes the participation of the people as part of the national values and principles of governance. Section 201(a) also outlines public participation as one of the principles of public finance alongside openness and accountability.

These requirements implore the citizens to hunger for information on matters of governance including land, and procurement issues that continue to nurture corruption. In so doing, accountability shall be enhanced and corruption lowered. While participating in the ballot is essential, continued vigilance is more important in the fight against corruption.

Conclusion

This paper has shed light on matters of corruption informed by literature. The varied definitions of corruption faces, as well as phases, have been given. In addition, questions on the elusive nature of corruption have been addressed, and amidst them, the question, is corruption wrong?

The different vices associated with corruption leading to the realization of its detriment to the common good are elucidated. While temporarily, the individual who gets rich from the proceeds of corruption may enjoy, the ultimate loss to the individual’s subsequent generations (due to lowered moral standards), as well as the integral loss to the environment, within which the individuals remain, prevail.

For there to be deterrence, punitive measures need to be put in place at the policy level to ensure an increase in the risk of the concerned corrupt individuals. Relevant Civil Society Organisations among them NGOs and FBOs have a continued significant role to prioritize effective, yet deliberate methods to combat corruption.

This paper also largely obliges the public, the greatest losers on matters of corruption, to be vigilant through public participation, and interest in public information, as ways of following up on their casting the ballot. While cultures are difficult to change, steps in the right direction of change are preferable to a docile wait-and-see attitude.