Introduction

Erikson (Aslan, 2008), Piaget (McLeod, 2022), Freud (Quinodoz, 2005), and Kohlberg (McLeod, 2013) inform scholarship on psycho-social, cognitive, psycho-sexual, and moral human development respectively. In societal development and growth, four stages come to play. The first is the Pre-Agrarian/neolithic Era which was characterized by human survival mechanisms including physical security. Tribal ties informed customs, norms, and traditions. Within this setup, societies were mainly nomadic, having a primitive economy. Hunting and gathering were key lifestyles (Bidyarthi, 2014).

The second is the Agrarian/neolithic era dating about 10,000 years ago, which started the domestication of animals. Primitive political organizations began showing some degree of social stability. The era also had socio-economic forces, including organized religion. Within it, reading and writing began. Trade was expanded and merchant life started. States and empires aimed at regulating the economy. These began together with cultural interactions and technological borrowing. Law and order became part of the human person. Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and later Chinese and Indian growth fall into this era. In summary, the four main components characteristic of this era were state building, trade, development of skills and tools, and cross-cultural interactions (Robson, 2010; Bidyarthi, 2014).

The Industrial Revolution is closer to the contemporary world dating between 1450 and 1750, and mainly in the 2nd half of the 18th Century (England: 1750–1760) (Mohajan, 2019). A notable economy was England. Manufacturing started giving rapid socio-economic, socio-political, and socio-cultural changes. Also, philosophical and scientific-technological developments were realized. Karl Marx and Max Weber remain significant actors in this era. The era is characterized by new productivity technologies, increased demands for manufactured goods, increased state revenues (taxes), and the need for labor exploitation creating the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Colonial powers seeking dominance, also emerge, leading to the dependency on the 3rd world (Mohajan, 2019).

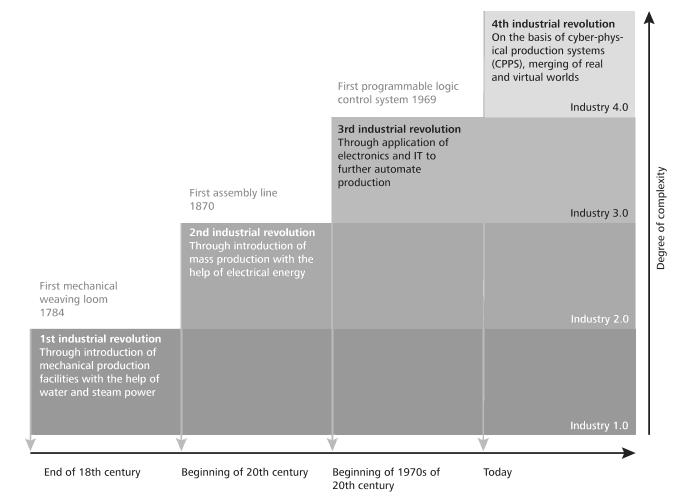

Finally, the Post Industrial Age or the Information Age is here with us. In the Industrial Age; the 1st and 2nd Industrial Revolutions allowed the society to move from mechanizing to assembly lines (mass production). This happened from the end of the 18th Century to the start of the 20th century (Acatech, 2012). In 1969, with the first programmable logic control system, the 3rd Industrial Revolution started. Automation became central. Today in the 4th Industrial Revolution, here-in referred to as the Information Age, the Cyber-Physical Production Systems (CPPS) have merged with the virtual worlds (Acatech, 2012). We are in an age where robotization, and computerization (computer-aided design and robots), create autonomous self-managing working systems, hence global value chains (Berger, 2014).

While human development shows almost clear demarcations in terms of change, society portrays a more complex state of events. This is because, human beings, starting from childhood, are socialized into a society (within a culture), while societies, on the other hand, do not have a macro guidance structure into which they are “socialized [;] rather, they must find their way in the world” (Psaltis, Gillespie, & Perret-Clermont, 2015). A significant aspect is a time taken to realize the change. In human beings, a span of 70 years allows one to move from being a toddler to an elderly individual (Aslan, 2008).

The change in society, however, dates from 30,000 years ago (300 centuries) and appears to only have moved through four major stages (Acatech, 2012; Bidyarthi, 2014). In addition, millions of human beings replicate each other in human development, so scholars can predict the path of the other human elements, with a large degree of precision and accuracy (Process Instruments, 2018). Society, on the contrary, appears to be one large mass, that is moving in some direction, with little chance of predictability (Psaltis, Gillespie, & Perret-Clermont, 2015). This appears to place scholars on a wild-goose chase, as they attempt to understand the changing trends of society.

Does this position then leave Africa guessing her position in societal development as well as her direction? Are there ways in which society, and Africa in this case, can predict the direction that she is moving, or is it at all times only possible to look backward? While change is slow yet inevitable (Bakamana & Kiingati, 2021 ), social transformation is certainly deliberate (Bakamana & Kiingati, 2021), and so can be predicted to some reasonable degree.

The latter allows the human person to effect change, and so have some form of responsibility in deciding the direction and the pace of change.

Based on this understanding, where is Africa in terms of societal development?

What does Africa need to do to effect positive change, for there to be an authentic and positive social transformation?

Kenya Conceptualised

The paper narrows down to the case of Kenya, an East African country, whose age after independence is 58 years. This country is part of the larger world population going through economic challenges following the Russia-Ukraine War (BBC News, 2022). She is also struggling with the aftermath of the COVID 19 depression (Barasa, 2020), a disease that is not totally behind us. In addition, to the two issues, Kenya is part of her African counterparts who still grapple with the negativities of ethnicity (Lesasuiyan, 2017), as well as high degrees of corruption. According to Faria, (2022), “Kenya scored 30 in the Corruption Perceptions Index as of 2021… out of 180 evaluated countries, [it] ranked close to the bottom of the list, at 128th”.

While the country has managed to go through 11 five-term periods in her over 55 years of independence, the last four elections are the ones that can be termed progressive, in terms of simulating freeness and fairness (Abuya, 2009; Kanyinga, 2014)

Generally, the one-party era elections oscillated from being semi-competitive to non-

competitive. The elections held between 1969 and 1988 under the one-party regime were semi-

competitive with elections that could pass as the party primaries serving as general elections.

These elections were not free…The multi-party elections that followed in 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2013 [including to a large extent the 2017 elections] have generally taken an ethnic and regional angle, catapulting the local level politics of the one-party era to the national level (Kanyinga, 2014, p. 116).

Kenyans are at the elections yet again, in barely thirty days to come. What needs to be done differently, for a socially transformative set of leaders to be in place? Even after elections, what do Kenyans need to do differently to ensure that their leaders are held accountable and that the individuals propel themselves towards continued sustainable development? In the discussion, Kenya’s development is informed by literature from itself and other countries in and outside the African region. This is geared towards avoidance of timewasting in attempting to re-invent the wheel.

Kenya’s History and Origins of her People

Kenya’s pre-colonial period could trace part of her population to Bantu migrations in the 3rd Millenium B.C.E., (Ehret, 2001; Ehret, 2015). Other peoples that are part of Kenya are the Nilotes whose origins are linked to South Sudan (Osuga, Odede & Odhiambo, 2020), and could be traced back to the times between 1650 and 1750.

Kenya’s pre-colonial period could trace part of her population to Bantu migrations in the 3rd Millenium B.C.E., (Ehret, 2001; Ehret, 2015). Other peoples that are part of Kenya are the Nilotes whose origins are linked to South Sudan (Osuga, Odede & Odhiambo, 2020), and could be traced back to the times between 1650 and 1750.

These two are the dominant large language groups and among them and other language groups, 42 ethnic communities are in Kenya (Balaton-Chrimes, 2021). According to Balaton-Chimes, voting patterns in Kenya, have apparent overtones of these divisions, hence the term tyranny of numbers. The media will call them voting blocks.

Currently, ethnic divisions are “Kikuyu (17.15%), Luhya (13.82%), Kalenjin (12.86%), Luo (10.47%), and Kamba (10.07%). Their total share of the population is 64.4%…[p.39 adds] Other numerically significant groups include the Kenyan Somalis (6.17%); Gusii (5.71%); Mijikenda (5.07%); and Meru (4.29%). The rest of the groupings, over 37, are so small numerically that their combined share of the population is less than 12%.” (Kanyinga, 2014, p. 12 & 39).

What critical issues need to be factored in as we seek a better Kenya?

Kenya’s Electioneering Phase

Campaign Discourse: Listening to Kenyans seeking leadership positions exposes an array of promises that in many ways are a replica of previous happenings (Carter Centre, n.d.). The persons concerned confirm what Plato in The Republic, called the “noble lie” (Muhammad, 2020), a strategy explored by Machiavelli (The Prince) when he speaks of lying and deception in politics (Machiavelli, 1532). In furthering the discourse, Mearsheimer (2011), categorizes five types of political lies:

(i) Inter-state lies; when political leaders target their deceptions at other countries to gain or retain some advantage over them;

(ii) Strategic cover-ups; when leaders mislead the public to cover up a personal scandal or a policy that has gone badly wrong;

(iii) Fearmongering; when political leaders spread exaggerated rumors and lies of impending dangers to deliberately arouse fear to manipulate the public to favor a specific policy or action;

(iv) Nationalist myths; when leaders employ national mythmaking to fuel solidarity by putting a country’s history in the best possible spotlight, even if this history is dark and bloody;

(v) Liberal lies; are used to justify odious behavior that conflicts with traditional ideals or protocols (Muhammad, 2020, p. 5).

The thrill, juxtaposed with shock, is the reaction of the masses to these “promises”. These reactions portray crowds that are excited at the presence of these leaders and thus respond in unison as if in agreement that a new Kenya shall certainly be re-born. It is often not exactly clear, what and why the rally attendees form large “congregations of these faiths”, and constantly avail themselves to part of the crowds.

Handouts (monies that politicians hand down to the crowds) are certainly part of the attraction to attend.

This may result in actual buying of votes or luring voters (Stokes, 2007; Linos, 2013; Robinson & Verdier, 2013). With a society that has a youth unemployment rate of 39.1 (Human Development Index-HDI, 2017 in Onchari, 2019) one expects large numbers of idlers. With the poverty rates of the populace of this country being at 45% (KNBS, 2007), it is also not surprising that people could follow leaders with the hope that they will realize some financial gain. Though not very clear, how it happens, words of rally attendees discussing how they fought over some money that was given by politicians, have been heard. Yet the question looms in the air, is the money received, equivalent to the time spent, the energies utilized, and the risk? Indeed some profit from monies given to them to distribute. Others cherish appointments when the leader is in power. Others still are placed at better tender bids, with their names being on the right side of the leader (Khalil, 2005). Yet again, what percentage of the general masses profit?

This may result in actual buying of votes or luring voters (Stokes, 2007; Linos, 2013; Robinson & Verdier, 2013). With a society that has a youth unemployment rate of 39.1 (Human Development Index-HDI, 2017 in Onchari, 2019) one expects large numbers of idlers. With the poverty rates of the populace of this country being at 45% (KNBS, 2007), it is also not surprising that people could follow leaders with the hope that they will realize some financial gain. Though not very clear, how it happens, words of rally attendees discussing how they fought over some money that was given by politicians, have been heard. Yet the question looms in the air, is the money received, equivalent to the time spent, the energies utilized, and the risk? Indeed some profit from monies given to them to distribute. Others cherish appointments when the leader is in power. Others still are placed at better tender bids, with their names being on the right side of the leader (Khalil, 2005). Yet again, what percentage of the general masses profit?

The nonverbal communication characterizing the campaign trail is of interest to this discussion.

There is a need for choppers to quicken the time spent from one rally to the other (Shulika, Muna, & Mutula, 2014). With over 3000 Kenyans killed on roads each year (Peden, Scurfield, Sleet, Mohan, Hyder, Jarawan & Mathers, 2004), it is safer for politicians to travel by air. In addition to that, there is a show of might, communicating power and authority (Hagmann & Péclard, 2010). This authority is also aggravated by their attire in addition to the vocal instruments that they use. Perhaps in-depth studies by marketers, sociologists, psychologists, and even political scientists, would inform better on the effects and relevance of each to the public.

Still, on nonverbals, we cannot ignore the paralinguistic cues: tone, pitch, and tempo. The confidence within which their words, phrases, and sentences are wrapped, is well-planned. The force and power that is in their voices, and the way these voices are projected, qualify these men and women to be termed very eloquent (Eaves & Leathers, 2017). This enhances the aura within which their mystique is realized.

In verbal communication, the choice of words, the blending of formal and informal language, use of cliches, are all an expression of a well-grounded person in language. Without a say, the repetition is real rhetoric, serving a political purpose: repeat the word so many times that it becomes a slogan or repeat the word so many times that the listeners get convinced that it is true (Chimbarange, Takavarasha, & Kombe, 2013). It is not surprising that crowds are carried away into ecstasy, with the same emotions as found in some congregational centers (Gonzalez, 2004).

What is yet to be understood, is the use of insults. It thrills yet shocks, how crowds easily buy into the language of insults (Kimotho & Nyaga, 2016).

What is yet to be understood, is the use of insults. It thrills yet shocks, how crowds easily buy into the language of insults (Kimotho & Nyaga, 2016).

This wave questions the education of the crowds on mannerisms; the inner values of the individuals within the crowds on matters of self-respect; honour and value for the neighbour; and inquires on the inner motivations of these persons when placed on the scale of being benevolent. It also interrogates the same persons in the area of intelligence; what do they expect of their leaders?

What is it that they expect of their country and themselves as citizens? Yet, inversely, the harangue appears to attract crowds and thrill them into admiring the leaders.

Campaign Crowd Behaviour calls for further analysis. Is the ecstasy of the crowd only in seeing the politician and the might surrounding the entourage, or does it have something to do with intoxication (Murunga, 1999)? May there be paid-up agitators that thrill the crowds, creating the right mood and atmosphere for the onlookers to be carried away into unruliness (Khanna, 2012)? Of greater interest are the rowdy youth whose focus is on making it impossible for the present political divide to make its entrance. The way these youth place their lives in danger and confrontation with armed and trained forces, raises several questions (Mutahi & Ruteere, 2019): Are they adequately paid as to risk their lives and health? Are they adequately intoxicated to be numb to the ugly outcomes that easily, again and again, befall them?

Anticipated Outcomes: Unless one is a very close family member of the person seeking power, or unless one is very well known by the top contenders, direct benefits of the individual who wins remain a mirage. In addition, countries flourish largely due to the policies that allow for the realization of specific directions in Government practice. Also, policies influence how budgets are spent and debts are treated (Maingi, 2017). International policies affecting trade and other openings are all influenced at the leadership level (Mwanzia & Strathdee, 2016). These factors inform any educated citizenry and determine ways in which voting patterns are done. However, evidently, in the developing world, ethnicity, emotional attachment, illusionary expectations, and gains, in addition to handouts, influence the way voting is done (Stokes, 2007). The eloquence of the politicians in addition to the individual’s use of verbal and nonverbal cues play a significant role (Eaves & Leathers, 2017).

Lessons from Past Campaign Periods: Indeed there is some growth since independence. A phase of a single party and life presidency had its pros and cons. The leadership then, like what was happening in many parts of the continent, called the citizens to cherish the end of colonial rule and start on self-rule (Murphy, 1986; Mwangi, 1998). Few addressed the issues of poverty and democracy.

As time went by, citizens demanded that they be part of the democratic systems through public participation (Nyaranga & Hongo, 2019). Through blood-shed and traumatic experiences, persons fought for yet other liberations (Osaghae, 2005). Through adherence to ethnic lords and tyranny of numbers, leaders got into power. Cries of rigging became a common discourse (Calas, 2007).

As time went by, citizens demanded that they be part of the democratic systems through public participation (Nyaranga & Hongo, 2019). Through blood-shed and traumatic experiences, persons fought for yet other liberations (Osaghae, 2005). Through adherence to ethnic lords and tyranny of numbers, leaders got into power. Cries of rigging became a common discourse (Calas, 2007).

Some African countries are still sadly at that stage. With time, however, with technological inventions, with a more educated electorate on matters of democracy and human rights, there is a positive wave toward freer and fairer elections (Elklit & Svensson, 1997). Local and international observers, add to the positive contribution.

Real Challenges

All these development phases are not guaranteed poverty reduction. Though challenges of the Ukraine-Russia war (BBC News, 2022) are a reality, though the COVID 19 pandemic menace (Barasa, 2020) cannot be overlooked, some things are on our docket to address

Corruption: It is not so much to be told of who is and who is not corrupt. Efforts to get the leaders to fight corruption have often fallen on deaf ears (Wamwere, 2010; Kempe, 2014). Very few would acclaim and offer themselves generously to the hanging loop. Just like poverty has and will never be minimized through the presence of more and more monies, fighting corruption will hardly be done by politicians; they are in many ways on the benefiting end of the corrupt deals (Kamau, 2009; Rugene, 2009). One government after another has come up stating well-crafted methods that they will use to fight corruption. Leaders have presented themselves as the cleanest and best placed to fight corruption (Mogeni, 2009). Each time they have entered into power however, the corruption discourse has appeared to take on an even uglier face (Mutua, 2014). Despite this, there are success stories from African countries, an example being Botswana (Hope & Chikulo, 2000).

Certainly, the fight against corruption calls for borrowing from the literature on fraud: According to Suh, Nicolaides, and Trafford (2019, p.5), “opportunity makes a thief…seeing is wanting”. The scholars go on to explain that for there to be fraud, there needs to be a likely offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian. For there to be a reduction of corruption, which indeed is a fraud, Clarke (2005), suggests that there be increased perceived effort crime; an increase in the perceived risk to a potential offender; reduce anticipated reward; reduce provocation, and remove excuses. These efforts are also supported by Morales et al., (2014). The persons in authority have the right mechanisms in their hands; are they willing to take up the task from the highest levels of the executive? Yet since those in leadership appear to have more verbal talk rather than action, what does each of us need to do differently at a personal, homestead, and even village level?

Negative ethnicity and nepotism (a more micro-organ of racism) are a portrayal of selfish divisive methods that create a “them” versus “us” mentality. This mentality, not only creates and sustains rifts but largely fails to realize and exploit one of the world’s largest resources: human capital.

It also nurtures undercutting tricks among people that should be pulling resources together. This tool has been used for a while, by faulty leaders who blind the populace while taking undue advantage of their ignorance. With such negativity, these leaders then feine ethnicity, blaming it for their failures concerning responsibility taking. They propel the human resource of their populace against other ethnic communities, rather than focusing it on wealth creation (Yieke, 2010). Atmospheres that should be friendly, are made hostile (Opondo, 2014). Evidently, the more negatively ethnicised a community is, the less the growth.

It also nurtures undercutting tricks among people that should be pulling resources together. This tool has been used for a while, by faulty leaders who blind the populace while taking undue advantage of their ignorance. With such negativity, these leaders then feine ethnicity, blaming it for their failures concerning responsibility taking. They propel the human resource of their populace against other ethnic communities, rather than focusing it on wealth creation (Yieke, 2010). Atmospheres that should be friendly, are made hostile (Opondo, 2014). Evidently, the more negatively ethnicised a community is, the less the growth.

Value Formation cannot be ignored in this discussion. Notable values include hard work, delayed gratification, and sustainability. In the pre-agrarian, agrarian, and post-agrarian epochs, the significant common string was hard work. Certainly, hard work is a prerequisite for development and wellness (Sharkey & Davis, 2008). In the information age, hard work, though this time mental, is core. However, there is a fallacy that people can make money sitted. There is an illusion that people can create wealth with the touch of a button. Of course, there is some truth in that; with computers and smartphones, people are doing so much, and some of it is value-adding and finance generating. Nevertheless, is this a giftedness for all? Is it all that there is to be done? Will all manage to place food on the table, by merely, sitting behind their laptops? Is it easy and light to sit behind computers and create content? Far from the lie, large percentages of young minds think it is the easy way out. This is the illusion that must be combated. There has never been a substitute for hard work, in any epoch, and this information is not an exception.

The second value that the write-up puts into perspective is delayed gratification. Max Weber and the Protestant Ethics (Marshall, 1982) made this clear. Results of the same characterize Western European economies, marked by other countries Germany. Simply put, “We cannot have a cake and eat it at the same time.” In life, one cannot start by being a spendthrift, surrounded by attitudes of consumerism and materialism, and still find it prudent to save (Hussein, Mohieldin, & Rostom, 2017). There is hardly any harm, and it is indeed just, that one enjoys the fruits of their hard labour. Persons that are involved in work and the subsequent abilities to generate, wisely yet justifiably, cherish and savor the sweetness of spending the fruits. A country’s growth of GDP is dependent on higher exports and lower imports. Manufacturing, production, and service delivery allow people to profit from earnings (Erkan, 2014). While the country’s leadership will inform on policies, at the bottom levels, people’s attitudes need to be well nurtured.

Sustainability is key to ensuring maximum positive recognition, appreciation, and exploitation of natural resources (Mutisya & Yarime, 2014). It is, however, mandatory that persons are aware that resources are not meant for just a generation. This means that the same resources need to be given ample time to re-generate (Reed, 2007). The non-re-generating resources have to be thus preserved to ensure that they are enjoyed by populations to come. With a fair treatment of the environment, that we are part of, nature will certainly pay back for indeed we are part of her.

Africans and in this case Kenyans, have to see to it that corruption is combated from its lowest levels. In addition, negative ethnicity coupled with nepotism has to be adequately nibbed. Similarly, value formation, with a special focus on hard work, delayed gratification, thinking, and acting sustainably, all have to factor into our everyday thinking, feeling, acting, and interactions. Only then can we experience growth.

Reality Check

As mentioned prior, unless the top leadership is going to be earned by a member of your immediate nuclear family, or a very close friend, the chances of you having direct benefits, are a mirage. That means that where we are before the election date, is largely where we shall be immediately and later after the election date. What we shall be doing is largely what we are doing currently. However, peace is highly essential during this phase. Chaos only adds to tribulations of poverty, and lack of basic needs, in addition to uncertainties majorly among those in the lowest earning cadre (Diwakar, 2018). The largest losses are within the domains of the very poor since it is here where imbalanced ratios between security forces and the populace are largely evident (Diwakar, 2018).

Eradication of poverty is hardly ever agitated by persons at the top of the beneficiary ladder (DFID, 2001-2010).

Protection of their properties, and continuation of the status quo, are among their top priorities (Mbandlwa, 2020).

It is human nature (Mwamba ngozi huvutia na kwake: the one who is tightening the drum hide, pulls it towards himself).

Hardly, do they exactly know what goes on at the bottom of the poverty lines, and hardly do they have constant reminders creating the urgency and precision with which poverty must be fought. Priorities differ with income.

We shall continue to pay taxes for that is our duty (Cummings, Martinez-Vazquez, McKee, & Torgler, 2005). Checks on these taxes and the way they are spent are our responsibility. Never shall leaders get monies off their pockets to ensure that the country develops, though often their discourse is on how much favours they do to us. Rather, from taxes, their expenses and remunerations are first factored in. As they execute their mandate of managing public coffers that they diligently and systematically contribute to, we have a responsibility to put them in check. When we abdicate this responsibility, only to resurface five years down the line to vote again, we suffer the consequences of poverty and deprivation (Richardson, Coterill, Squires, & Askew, 2014). In our little small ways, each has a responsibility at the home, village, sub-county, county, and national level, to first ensure that one votes, and not stay at home lamenting; that one votes from reason and not passion; that one stays awake keeping the leader on toes at all levels and at all times. The starting point is information, for indeed we are at the age of information.

NB: TRUE WORK TOWARDS SELF-EMANCIPATION FROM POVERTY IS MY LIFELONG RESPONSIBILITY. INDEED, THAT IS TRUE SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION

References

Abuya, E. (2009). Consequences of a flawed presidential election. Legal Studies, 29(1), 127-158. DOI:10.1111/j.1748- 121X.2008.00110.x

Acatech. (2012). National Academy of Science and Engineering. Recommendations for implementing the strategic initiative INDUSTRIE 4.0, August Available on the Internet <http://www.acatech.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Baumstruktur_nach_Website/Acatech/ root/de/ Material_fuer_Sonderseiten/Industrie_4.0/Final_report__Industrie_4.0_accessible.pdf>.

Aslan, E. (2008). An investigation of Erikson’s psychosocial development stages and ego identity processes of adolescents with respect to their attachment styles. (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis). Selçuk University Institute of Social Sciences, Konya.

BBC News. (2019). “Ukraine and Russia Agree to Implement Ceasefire.” BBC News, December 10. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50713647

Bakamana, D. B & Kiingati, J. B. (2021). Dynamics of Social Transformation: Myth and Reality in Africa. Journal of African Interdisciplinary Studies, 5(8), 76– 101.

Balaton-Chrimes, S. (2021). Who are Kenya’s 42(+) tribes? The census and the political utility of magical uncertainty, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 15 (1), 43-62, DOI:10.1080/17531055.2020.1863642. Available at https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2020.1863642

Barasa, E., (2020). Assessing the Hospital Surge Capacity of the Kenyan Health System in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medarxiv, 1–24 (2020).

Berger, R. (2014). Industry 4.0: A driver of innovation for Europe. Available on the Internet: <http://www.think-act.com/blog/2014/industry-4-0-a-driver-of-innovation-for-europe/>

Bidyarthi, D. (2014). Different landmarks on the way from industrial to knowledge society: a holistic view. Conference Paper. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304627287

Calas, B. (2007). From rigging to violence. The general elections in Kenya, 165-185.

Carter Centre (The). (n.d.) Youth and Women’s Consultations on Political Participation Findings and Recommendations. Available at https://www.cartercenter.org

Chimbarange, A., Takavarasha, P., & Kombe, F. (2013). A critical discourse analysis of President Mugabe’s 2002 address to the world summit on sustainable development. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(9), 227-288.

Clarke, R. V., 2005. Seven misconceptions of situational crime prevention. In Tilley, N. (Ed.), Handbook of Crime Prevention and Community Safety. Willan Publishing, Cullompton, pp. 39-70.

Cummings, R.G. Martinez-Vazquez, J., McKee, M., and Torgler, B. (2005) ‘Effects of Tax Moral on Tax Compliance: Experimental and Survey Evidence’ CREMA Working Paper No 2005 29

Department for International Development (DFID). (2001-2010). The Politics of Poverty: Elites, Citizens, and States- OECD. Available at https://www.oecd.org

Diwakar, V. (2018). Understanding Poverty in Kenya: A Multidimensional Analysis. Available at https://cdn.sida.se

Eaves, M. H., & Leathers, D. (2017). Successful nonverbal communication: Principles and applications. New York: Routledge.

Ehret, C. (2001). Bantu expansions: Re-envisioning a central problem of early African history. International Journal of African Historical Studies, 34(1), 5–41.

Ehret, C. (2015). Bantu history: Big advance, although with a chronological contradiction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1517381112. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283326421

Elklit, J., & Svensson, P. (1997). The rise of election monitoring: What makes elections free and fair? Journal of democracy, 8(3), 32-46.

Erkan, B. (2014). The importance and determinants of logistics performance of selected countries. Journal of Emerging Issues in Economics, Finance, and Banking, 3(6), 1237-1254.

Faria, J. (2022). Corruption perception in Kenya 2012-2021. Available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/1286269/corruption-perception-index-in-kenya.

Gonzalez, A. (2004). Jawole Zollar’s Praise House and the Ecstasy of Black Church Ritual. Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, 123-136.

Hagmann, T., & Péclard, D. (2010). Negotiating statehood: dynamics of power and domination in Africa. Development and change, 41(4), 539-562.

Hope, K. R., & Chikulo, B. C. (2000). Introduction. In K. R. Hope & B. C. Chikulo (Eds.), Corruption and development in Africa: Lessons from country case-studies (pp. 1– 13). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hussein, K., Mohieldin, M., & Rostom, A. (2017). Savings, financial development, and economic growth in the Arab Republic of Egypt revisited. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (8020).

Kamau, M. (2009, December 4). MPs corrupt at the expense of Kenyans says Karua. East African Standard. Available from http://www.marsgroupkenya.org/multimedia/?StoryID=274443

Kanyinga, K. (2014). Kenya: Democracy and Political Participation: A review by AfriMAP, Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa and the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Nairobi. Available at https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org

Kempe, R. H. (2014). Kenya’s corruption problem: causes and consequences, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 52:4, 493-512, DOI: 10.1080/14662043.2014.955981. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2014.955981.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Basic Report on Well-Being in Kenya. Nairobi: Regal Press.

Khalil T. M. H. (2005). Debate, Review of African Political Economy, 32, 104-105, 383-393, DOI: 10.1080/03056240500329270

Khanna, A. (2012). Seeing citizen action through an ‘unruly’ lens. Development, 55(2), 162-172.

Kimotho, S., & Nyaga, R. (2016). Digitized ethnic hate speech: Understanding effects of digital media hate speech on citizen journalism in Kenya.

Lesasuiyan, R. (2017). Analysis of the Impact of Negative Ethnicity on National Policy in Kenya: A Case of Molo Sub-County. M.A.Thesis. Available at http://erepository.ounbi.ac.ke.

Linos, E. (2013). Do conditional cash transfer programs shift votes? Evidence from the Honduran PRAF. Forthcoming in Electoral Studies.

Machiavelli, N. di B. dei. (1532). The Prince. (Bull, G., Ed.) (1999th ed.). Penguin Books. Available at https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822381570-002

Maingi, J. N. (2017). The impact of government expenditure on economic growth in Kenya: 1963 2008. Advances in Economics and Business, 5(12), 635-662.

Marshall, G. (1982). In Search of the Spirit of Capitalism. An Essay on Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic Thesis. In In Search of the Spirit of Capitalism. an Essay on Max Weber’S Protestant Ethic Thesis. Columbia University Press.

Mbandlwa, Z. (2020). Challenges of African Leadership after the Independency. Solid State Technology 63(6), 6769-6779. Available at https://www.researchgate.net.

McLeod, S. (2013). Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development. Available at https://www.simplypsychology.org/kohlberg.html.

McLeod, S. (2022). Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development: Background and Key Concepts of Piaget’s Theory. Available at https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2011). Why Leaders Lie: The Truth about Lying in International Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mogeni, D. (2009, February 5). Why corruption persists in Kenya. Daily Nation. Available from http://www.nation.co.ke/oped/Opinion/-/440808/525272/-/42v0lp/-/index.html

Mohajan, H. K. (2019). The First Industrial Revolution: Creation of a New Global Human Era. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 5(4), 377-387. Available at http://www.aiscience.org/journal/jssh.

Morales, J., Gendron, Y., Guénin-Paracini, H., (2014). The construction of the risky individual and vigilant organization: A genealogy of the fraud triangle. Accounting, Organizations and Society 39, 170-194

Muhammad, I. (2020). On Political Lies. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342282575.

Murphy, J. F. (1986). Legitimation and Paternalism: The Colonial State in Kenya. African Studies Review, 29(3), 55-66.

Murunga, G. G. R. (1999). Urban violence in Kenya’s transition to pluralist politics, 1982-1992. Africa Development, 24(1), 165-198.

Mutahi, P., & Ruteere, M. (2019). Violence, security, and the policing of Kenya’s 2017 elections. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 13(2), 253-271.

Mutisya, E., & Yarime, M. (2014). Moving towards urban sustainability in Kenya: a framework for integration of environmental, economic, social and governance dimensions. Sustainability Science, 9(2), 205-215.

Mutua, M. (2014, May 25). Why corruption and not terror is the country’s worst enemy. Standard on Sunday, p. 15.

Mwangi, E. (1998). Colonialism, self-governance, and forestry in Kenya: Policy, practice, and outcomes.

Mwanzia, J. S., & Strathdee, R. C. (2016). Participatory Development in Kenya. London: Routledge.

Nyaranga, M. S., Hao, C., & Hongo, D. O. (2019). Strategies of integrating public participation in governance for sustainable development in Kenya. Public Policy Admin Res, 9.

Onchari, D. (2019). The relationship between corruption and unemployment rates in Kenya. Akademi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 6(17), 309-318.

Opondo, P. A. (2014). Ethnic politics and post-election violence of 2007/8 in Kenya. African Journal of History and Culture, 6(4), 59-67.

Osaghae, E. E. (2005). The state of Africa’s second liberation. Interventions, 7(1), 1-20.

Osuga, E., Odede, F. A., & Odhiambo, G. (2020). The Origin, Migration, and Settlement of Ethnic Groups in Yimbo of Western Kenya from 1800-1895. International Journal of Advanced and Multidisciplinary Social Science 6(2), 54-59. DOI: 10.5923/j.jamss.20200602.02

Peden M., Scurfield, R., Sleet, D., Mohan, D., Hyder, A. A., Jarawan, E., & Malhers, C. (2004). World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Process Instruments (2018). PiTechnical Note 10. Accuracy, Precision, Reproducibility, Repeatability, and Resolution: What do they mean? Available at http://www.processinstruments.cn

Psaltis, C., Gillespie, A., & Perret-Clermont, A.N. (2015). Introduction 1. In Psaltis, C. Gillespie, A. & Perret-Clermont, A.N. (Eds.) Social Relations in Human and Societal Development. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Quinodoz, J.-M. (2005). Reading Freud: A Chronological Exploration of Freud’s Writing (trans: Alcorn, D.). London: Routledge.

Reed, B. (2007). Shifting from ‘sustainability to regeneration. Building Research & Information, 35(6), 674-680.

Richardson, L., Coterill, S., Squires, G., & Askew, R. (2014). Responsible citizens and accountable service providers? Renegotiating the contract between citizen and state. Environment and Planning A, 46, 1716-1731. DOI:10.1068/a46127.

Robinson, J., Verdier, T., 2013. The political economy of clientelism. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(2), 260-291.

Robson, A. J. (2010), A bioeconomic view of the Neolithic transition to agriculture, Canadian Journal of Economics 43(1), 280-300.

Rugene, N. (2009, May 16). Bribery in Kenya’s parliament. Daily Nation. Available from http://www.nation.co.ke/News/-/1056/599016/-/u6adu9/-/index.html.

Sharkey, B. J., & Davis, P. O. (2008). Hard work: defining physical work performance requirements. Mitcham-Australia: Human Kinetics.

Stokes, S. (2007). “Political Clientelism.” In C. Boix and S. C. Stokes (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics (pp. 604-627), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shulika, L. S., Muna, W. K., & Mutula, S. (2014). Monetary clout and electoral politics in Kenya-the 1992 to 2013 presidential elections in focus. Journal of African Elections, 13(2), 196-215.

Suh, J. B., Nicolaides, R., & Trafford, R. (2019). The effects of reducing opportunity and fraud risk factors on the occurrence of occupational fraud in financial institutions. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 56, 79-88.

Wamwere, K. (2010). Top leadership must be in the forefront if the battle on corruption is to be won. Available from http://www.nation.co.ke/oped/Opinion/-/440808/1046170/-/nw15ccz/-index.html.

Yieke, F. A. (2010). Ethnicity and development in Kenya: Lessons from the 2007 general elections. Kenya studies review, 3(3), 5-16.